Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Existential. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines that word as “of, relating to, or affirming existence.” It is not a word to be taken lightly. It has weight — gravitas, some might say. It was the central focus of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. It might not seem like it has much to do with data centers, but it does in this respect. The corporations which extract and sell methane gas to power thermal generating stations see the vast increase in demand for electricity for data centers as a godsend. Those who believe reducing carbon and methane emissions is essential to preserving human life on planet Earth see it as making that goal nearly impossible.

The two positions are irreconcilable. If we burn methane to power data centers, we risk making life on Earth impossible for millions — perhaps billions — of people. If we preserve the environment, we may have to do without the blessings of artificial intelligence. Some might suggest what we really need is a greater supply of actual intelligence.

Arielle Samuelson, writing for the blog HEATED, details how the methane producers have visions of sugar plums dancing in their heads as they calculate the profits they can make by supplying fuel to new thermal generating plants. One roadblock is America’s electrical grid. It takes too long to get permission to connect new sources of energy, so why not bypass the grid entirely and just build generating stations next door to data centers? Elon Musk, in his usual understated way, has named his gigantic new data center in Memphis “Colossus.” When complete, it may need as much as 1 gigawatt of electricity — the customary output of a new thermal generating station.

As large language models like ChatGPT become more sophisticated, experts predict the demand for energy in the US will grow by a “shocking” 16% in the next five years. Tech giants like Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet have increasingly turned to nuclear power plants or large renewable energy projects to power data centers that use as much energy as a small town, Samuelson writes. But those cleaner energy sources will not be enough to meet the voracious energy demands of AI, analysts say. To bridge the gap, tech giants and fossil fuel companies are planning to build new gas power plants and pipelines that directly supply data centers. And they increasingly propose keeping those projects separate from the grid, fast-tracking gas infrastructure at a speed that can’t be matched by renewables or nuclear.

Data Centers As The Saviors Of The Methane Industry

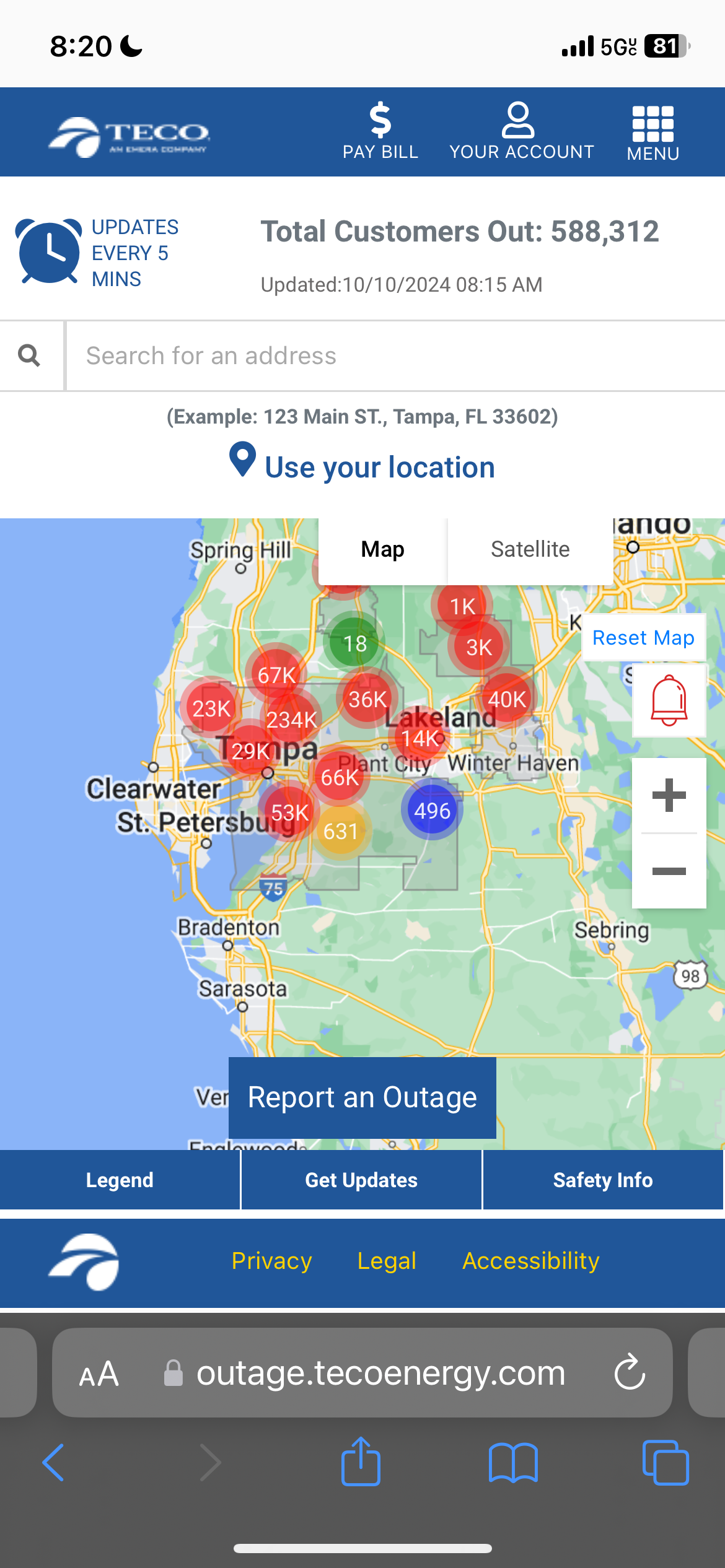

The growth of AI has been called the “savior” of the methane industry. In Virginia alone, the data center capital of the world, a new state report found that AI demand could add a new 1.5 gigawatt gas plant every two years for 15 consecutive years. Last week, Exxon announced it is building a large methane-fired generating station that will directly supply power to data centers within the next five years. But not to worry, folks. Exxon’s new power plant will use carbon capture technology, so no excess carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere. That, of course, completely ignores the climate impacts of methane itself, which is 80 times more powerful as a climate heating agent than carbon dioxide. It also conveniently ignores the fact that large-scale carbon capture is not currently a commercially viable technology and is not likely to be anytime soon.

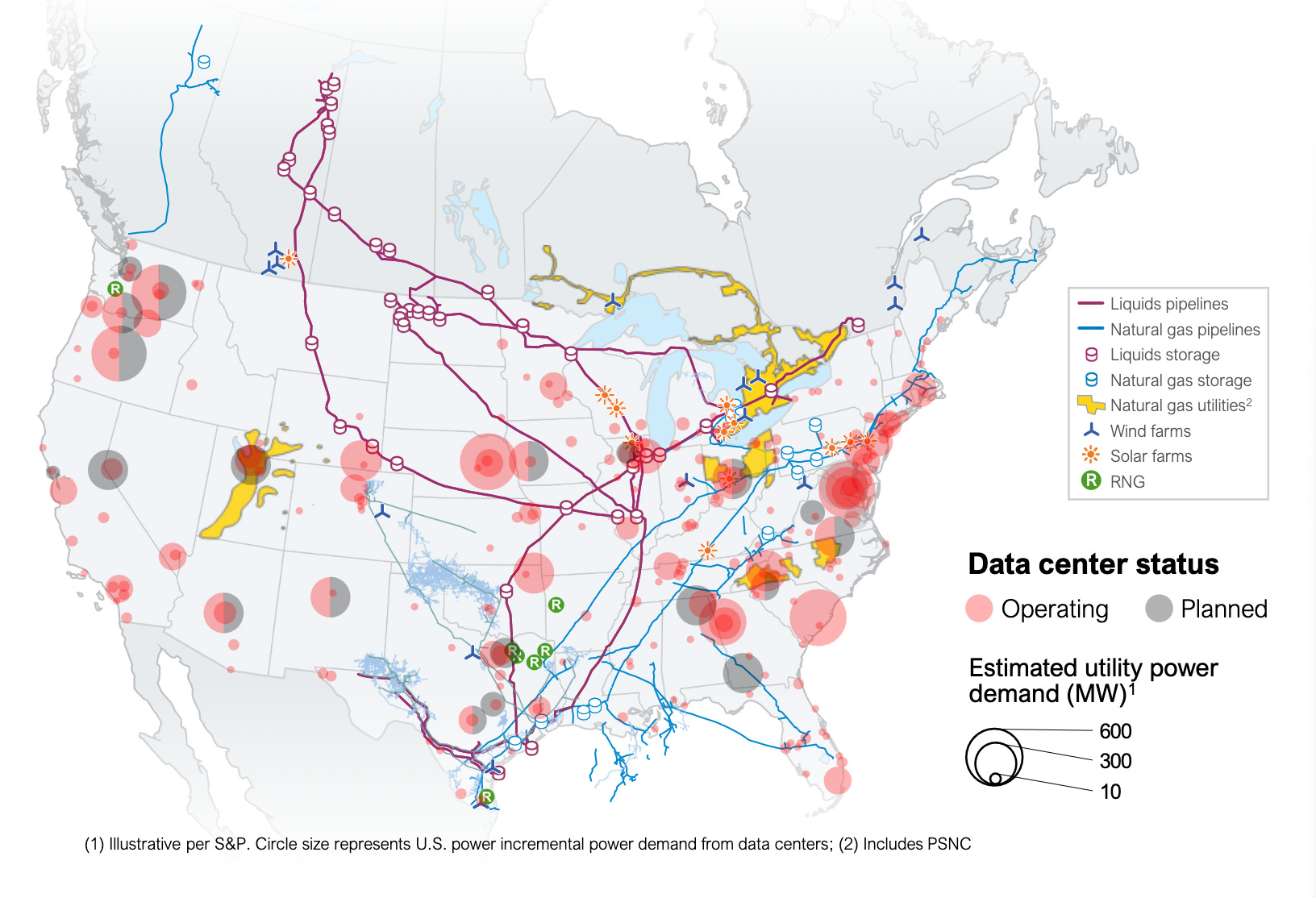

Chevron also announced it is preparing to sell methane to an undisclosed number of data centers. “We’re doing some work right now with a number of different people that’s not quite ready for prime time, looking at possible solutions to build large-scale power generation,” said CEO Mike Wirth at an Atlantic Council event. The opportunity to sell power to data centers is so promising that even private equity firms are investing billions in building energy infrastructure.

The companies which will benefit the most from an AI methane boom, according to S&P Global, are pipeline companies. This year, several of them told investors that they were already in talks to connect their networks directly to on-site gas power plants at data centers. “We, frankly, are kind of overwhelmed with the number of requests that we’re dealing with, ” Williams CEO Alan Armstrong said on a call with analysts. The pipeline company, which owns the 10,000 mile Transco system, is expanding its existing pipeline network from Virginia to Alabama partly to “provide reliable power where data center growth is expected,” according to Williams.

Energy Transfer announced earlier this month that its new $2.7 billion project in the Permian Basin will help establish the company “as the premier option to support power plant and data center growth in the state of Texas.” In its most recent earnings call, the company said it has received requests from more than 40 proposed data centers in 10 states to build pipelines connecting to their larger gas network. Enbridge announced this quarter that it added 50 megawatts of gas power to data centers in Utah alone. Meanwhile, Kinder Morgan is building a $3 billion expansion to its Southern Natural gas system to help meet the growing power demand.

The flurry of proposed pipelines is a result of tech companies prioritizing creating their own energy, rather than relying on an increasingly overwhelmed electric grid. “They recognized that data centers are unsustainable in terms of just being able to plug it into the grid,” said Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at Public Citizen. He believes the methane industry is aggressively lobbying the tech industry to use fossil fuels. Companies like Microsoft, Google, and Apple “pioneered a generation ago the need for sustainability,” he said. “But now I see Big Tech being a lot more comfortable with natural gas as a partner. And that should be very concerning.”

Altogether, S&P Global Ratings estimates that data centers will lead to additional demand of between 3 to 6 billion cubic feet of gas per day by 2030 — equivalent to the gas consumption of the entire state of Florida. That amount of gas could add anywhere from 164,000 to 329,000 metric tons of polluting greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere every day. But S&P Global analysts say that the significant energy needs of data centers cannot be met by renewable energy alone.

Cutting Out Utility Companies

“On the current trajectory of gas buildout, net zero by 2050 is dead,” said Tyler Norris, a former solar power developer and current doctoral student studying electric power systems at Duke University. “There is just no possible way to achieve net zero when you’re adding tens to even hundreds of gigawatts of more gas power to the system.” The methane industry argues that it is cleaner than coal and therefore better for the climate. But according to the United Nations, global gas power plant emissions have to be cut by 28 to 78% to avoid the worst effects of the climate crisis

By removing utilities as the middlemen in the power supply industry, methane advocates say they can circumvent many of the federal regulations that slow down pipeline construction today. Those environmental regulations may also soon be loosened by the government itself. Last week, E&E News reported that President Biden is considering issuing an executive order to fast track construction of AI data centers in the name of national security.

Whether or not the AI bubble bursts eventually, data centers have tipped the scales in favor of fossil fuels. Tech companies are “going to go with whoever comes to the table with the most affordable and reliable energy option,” said Tyler Slocum of Public Citizen. “And increasingly, that means that protecting the climate and the Earth fall by the wayside.”

The Case For Powering Data Centers With Renewables

That is a rather dire forecast by Slocum. Fortunately, Bill McKibben wrote on his blog The Crucial Years this week about a new study that takes the discussion of power for data centers down to the granular level and finds that if these data centers are actually going to get built anytime soon, the best bet is to put up solar farms next door. Building new methane-powered thermal generating plants takes a number of years. But if you have a “co-located microgrid,” it can be installed quite quickly. “Estimated time to operation for a large off-grid solar microgrid could be around 2 years (1-2 years for site acquisition and permitting plus 1-2 years for site buildout), though there’s no obvious reason why this couldn’t be done faster by very motivated and competent builders.”

The analysis is extensive and it finds solar microgrids that serve co-located data centers are price competitive with co-located methane thermal generation. In some cases, the cost is less and in some cases it is slightly higher, but as McKibben points out, most of these companies building data centers have their headquarters in places like Washington and California that are filled with environmentally committed workers and investors. “We should be able to organize some pressure on them to do the right thing. It’s not the perfect thing. In a rational world we’d postpone the glories of AI long enough to power up all the heat pumps and cars from renewable electricity first. But if they get expertise building solar farms for their data centers, the experience may turn these behemoths into better crusaders for clean energy,” McKibben writes.

“Here’s the final bottom line from the report,” he says. “Off grid solar microgrids offer a fast path to power AI data centers at enormous scale. The tech is mature, the suitable parcels of land in the US Southwest are known, and this solution is likely faster than most, if not all, alternatives, The advantages to whoever moves on this quickly could be substantial.”

Existential Is As Existential Does

The authors of the study even delved into a “what if there were no subsidies?” scenario, which was wise, since the new mantra favored by Elon Musk is that nobody should get any subsidies at anytime for anything.

“We were curious how these costs might look in a scenario with fewer market distortions: no investment tax credit, extremely easy to build projects, no tariffs on equipment, etc. We call this our Abundance Scenario. To test this, first we eliminated the Investment Tax Credit. Next, as a comp for “easy to build” and “no tariffs,” we took solar and battery total installed system costs (pre-subsidies) reported from China (about 50 cents/watt for solar and $145/kWh for batteries) as an aggressive low case for build costs.

“We then ran those costs across various levels of redundancy. We find that, at these costs and if willing to sacrifice redundancy entirely, one could build a system that serves 95% of the 24/7 flat data center load with just solar and storage at a cost equal to off grid gas turbines. And even with the 1.25x generator capacity, a 75% renewable (100% of load served) system is just $90/MWh versus $86/MWh for off-grid gas turbines.”

The question then becomes, is a sustainable Earth worth an extra $4 per MWh? Questions don’t get much more existential than that.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy