Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

In the middle of 2024, I documented the remarkable disappearance of claims of environmental virtue from the websites and social media of Canadian oil and gas companies and the lobbying groups they employed. Overnight, the degree of factual accuracy on their public sites went up by a remarkable amount. Why? Because Bill C-59, titled the Fall Economic Statement Implementation Act, 2023, received Royal Assent on June 20, 2024, officially becoming law in Canada.

That seems like an odd reaction. Why would companies rip their greenwashing from public view over an economic implementation act? Well, Bill C-59 grants the Competition Bureau new powers to scrutinize and take enforcement action against companies that make false or misleading environmental claims about their products, services, or business practices. Businesses are now required to substantiate their environmental claims with “adequate and proper testing” or “adequate and proper substantiation in accordance with internationally recognized methodology.” Canada is following, quite reasonably, in the footsteps of the United States, Europe and China, its three biggest trading partners.

As a result, right-wing media, fossil fuel companies, and fossil fuel PR groups put out press releases with words like “draconian” and “censorship.” They also ditched all the BS they had online for years claiming the virtues of carbon capture, the wonders of how much they’d already cleaned up their oil and gas extraction and processing, and quite a lot of the nonsense they promoted about their homeopathic investments in wind turbines and solar farms.

But a different group of firms should be considering the implications of this, the people promoting fuel cells and hydrogen electric vehicles in Canada. It’s clear that their claims of hydrogen vehicles being low emissions are not supported by “adequate and proper testing” or “adequate and proper substantiation in accordance with internationally recognized methodology.” Quite the opposite.

Before explaining why, let’s have a look at some of the organizations which should be concerned about this and what their material says. Let’s start with Canadian-headquartered bus manufacturer New Flyer and head through a list that includes global consultancy Deloitte, a major Canadian transit agency, transit “think tank” CUTRIC, and of course Ballard power.

I could go on. Brampton accepted and recommended action on CUTRIC’s indefensibly bad blended hydrogen and battery electric bus fleet. Edmonton is buying hydrogen buses and making emissions cuts promises. HTEC is expanding with hydrogen trucks and its refueling system.

All of them are promising zero emissions, and that mostly means greenhouse gases. They are promising that hydrogen vehicles will eliminate greenhouse gas emissions.

It isn’t remotely true in any of the planned deployments and it isn’t remotely true in the future either. Every single claim above is in violation of Bill C-59. How can I say that? Hydrogen, when it goes through a fuel cell, emits only water, after all.

Well-to-wheel (WTW) emissions have emerged as the global benchmark for assessing the environmental impact of vehicles because it provides a comprehensive view of emissions across the entire energy lifecycle. Unlike the narrower tank-to-wheel metric, which only measures emissions during vehicle operation, well-to-wheel considers both upstream emissions — such as those from fuel extraction, refining, or electricity generation — and downstream emissions during use. This approach ensures transparency and prevents the misrepresentation of low-emission technologies. International bodies, including the International Energy Agency and the European Union, advocate for well-to-wheel analysis, as it aligns with lifecycle thinking and highlights the need to decarbonize energy sources alongside promoting zero-emission vehicles. The shift to well-to-wheel is critical for informed policymaking, as it helps governments and industries prioritize truly sustainable solutions rather than focusing solely on operational emissions. Even the very much lagging International Maritime Organization adopted well-to-wheel as the standard a few years ago.

Don’t buy that it’s broadly accepted? How about these organizations, standards, and models?

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

- ISO 14040/14044: Life Cycle Assessment standards for evaluating full lifecycle emissions.

- ISO 14067: Carbon footprint standards emphasizing well-to-wheel (WTW) methodologies.

- European Union (EU)

- Renewable Energy Directive (RED II): Mandates WTW analysis for biofuels, renewable fuels, and hydrogen.

- Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy: Lifecycle emissions focus for mobility technologies.

- International Energy Agency (IEA)

- Global reports and policies consistently using WTW analysis, e.g., Global EV Outlook.

- United Nations Framework

- UNFCCC Guidelines: Comprehensive emissions accounting for climate strategies.

- UNEP Life Cycle Initiative: Advocates lifecycle thinking and WTW methodologies.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- GREET Model: Calculates WTW emissions for fuels and vehicles.

- World Resources Institute (WRI)

- Greenhouse Gas Protocol: Lifecycle emissions methodologies aligning with WTW principles.

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT)

- Reports on WTW emissions of alternative fuels and decarbonization strategies.

- World Bank

- Sustainable transport studies promoting lifecycle emissions approaches, including WTW.

No court in Canada would consider anything except well-to-wheel to be an “internationally recognized methodology.” Tank-to-wheel just doesn’t cut it.

Hydrogen fails well-to-wheels over and over again. Every claim about it being zero emissions, or frankly even low emissions, is false.

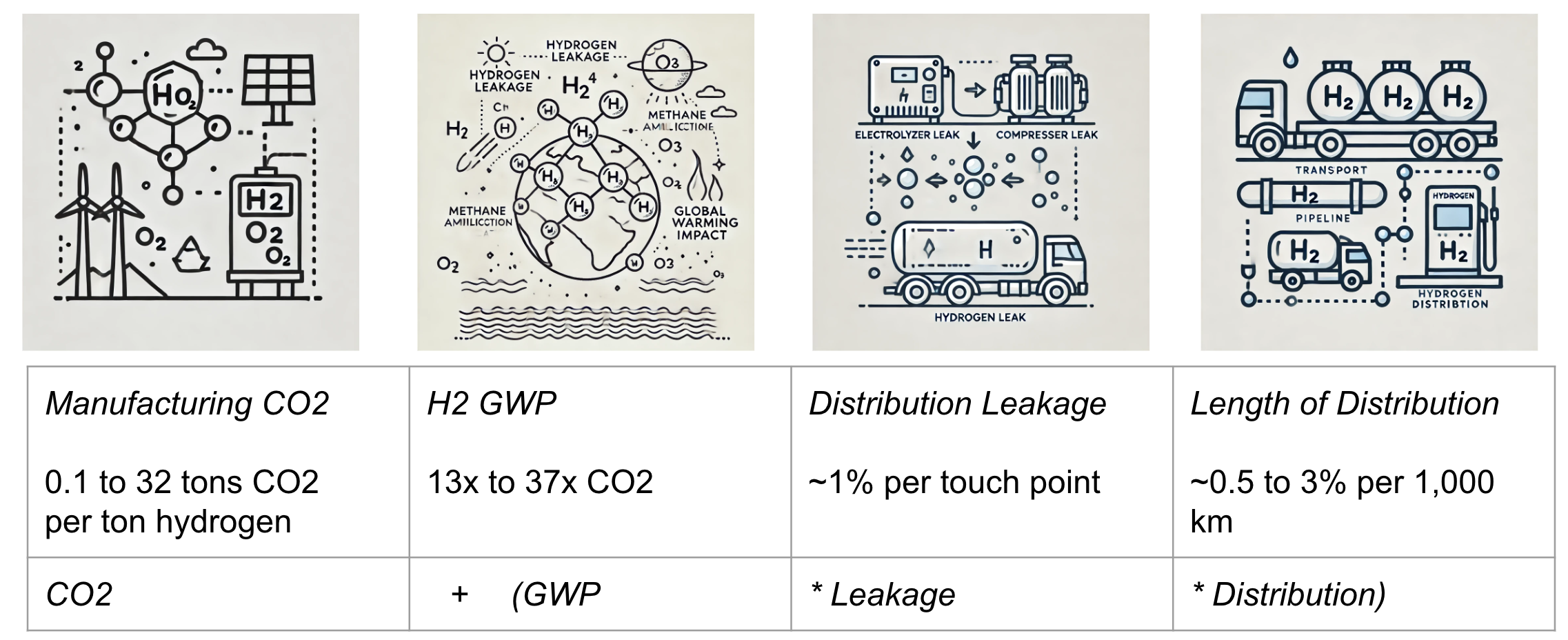

There are four elements to the hydrogen emissions claims which have to be considered: method of manufacturing, global warming potential, degree of leakage, and location of manufacturing.

Well-to-wheel means that how hydrogen gets made matters. It’s possible to make a claim that hydrogen is low emissions if it is made from low-carbon electricity, ignoring the rest of the conditions. The lowest-emissions hydrogen possible comes out of the ground, but there are zero proven reserves, so let’s stick with current approaches, and in that space, hydrogen electrolyzed out of water in industrial-scale plants with low-carbon electricity wins. This category includes feedstock upstream emissions, like methane leakage from the natural gas supply chain and fuel for electricity.

Assuming an industrial-scale plant near Winnipeg manufacturing hundreds of thousands of tons of hydrogen with Manitoba’s 1.3 grams of CO2e/kWh a year, firmed electricity, you could expect to see hydrogen having around 0.05 tons of CO2e per ton of hydrogen. That’s well under the Hydrogen Science Coalition’s threshold of a ton of CO2e per ton of hydrogen. It’s arguably zero emissions with a bit of wiggle room. Even at an inefficient, small electrolysis facility at the transit garage, that would only turn into 0.1 tons of CO2e per ton of hydrogen.

Originally, Winnipeg planned to do that, but then the price tag for both the equipment and the electricity hit, so they pivoted to steam reformation of methanol — aka wood alcohol — to make hydrogen. Wood has nothing to do with it, as methanol is made from natural gas or coal. Given the emissions of manufacturing methanol, throwing away 55% of the energy with the carbon, making carbon dioxide from steam reformation, and then getting a little back because fuel cell buses are more efficient than diesel buses, the emissions are about 3.2 times higher than diesel.

3.2 times higher than diesel would not be construed in any court of law to be zero emissions.

In Ontario, the apparent plan is to acquire hydrogen from firms like Enbridge, which has a serious conflict of interest regarding its seat on CUTRIC’s Board regarding hydrogen buses. If it were made in Sarnia from natural gas, by far the dominant source of hydrogen in the province, every ton of hydrogen would have 10-12 tons of carbon dioxide from manufacturing it.

10–12 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of fuel would not be construed in any court of law to be zero emissions.

If it were made with Ontario’s grid electricity of 35 grams CO2e/kWh at an industrial facility, it would have about 1.1 tons of CO2 per ton of hydrogen, just over the Hydrogen Science Coalition’s threshold. If it were made at a transit garage, that would be about 2 tons of CO2e per ton of hydrogen. That might be arguable, if nothing else were in play.

It’s possible to eliminate about 85% of the CO2e from hydrogen made from natural gas by bolting on expensive and energy hungry carbon capture and sequestration technologies. That would reduce the CO2 per ton town to 1.5 to 1.6 tons. Maybe that would be defensible, if nothing else were in play.

But let’s get into the next part of the problem, the global warming potential of hydrogen. Yeah, it’s a greenhouse gas. Not directly like carbon dioxide, methane or refrigerants, but indirectly. What does that mean? It means it prevents the potent greenhouse gas methane from breaking down in the atmosphere as quickly, keeping its roughly 90 times carbon dioxide potency around longer. Hydrogen bonds with something methane bonds with, but with more chemistry, so methane is CO2-blocked and keeps heating the atmosphere.

That turns into 37 times the heating of carbon dioxide over 20 years and 13 times over 100 years.

Don’t believe this? How about believing a multi-author peer-reviewed paper in Nature, “A multi-model assessment of the Global Warming Potential of hydrogen?” People started wondering about hydrogen in the atmosphere a decade or so ago and when scientists start wondering they start experiments and spin up big models. Now we have a pretty good idea that hydrogen just doesn’t waft to the top of the atmosphere and get stripped away by the solar wind, it does exactly what it does everywhere else, react with other things as much as possible. It’s a social butterfly and will accept a coffee or drinks invite from pretty much anything.

No problem, let’s just keep it in the box. Yeah, wait. Hydrogen is the second smallest molecule in the universe according to physics, which considers helium a molecule even though it’s just an atom. Chemistry doesn’t, so by a reasonably big chunk of science, hydrogen is smallest. I consider it a bit of a semantic concern because the question is one of physics, not chemistry: does it leak through stuff or not? And the answer is that it does.

Up until recently, this has strictly been a safety issue. Hydrogen, after all, explodes really easily, a lot more easily under a lot more conditions than natural gas. It’s an industrial feedstock used in industrial facilities to refine crude oil, make fertilizer, make methanol and do a few other small things. In those settings, the question is whether there’s enough hydrogen to explode, and a lot of care is taken to ensure that there is good ventilation, hydrogen losses aren’t too expensive and there are hydrogen sensors that scream loud warnings if concentrations build up so workers can run away.

But we haven’t really cared if it leaked if it didn’t blow up and injure industrial workers before. Now we do because we know it’s a greenhouse gas. Every ton of hydrogen that leaks is suddenly like 37 tons of carbon dioxide. We make about a hundred million tons of hydrogen a year, so if 10% of it leaked, it would be like 370 million tons of carbon dioxide. That’s a lot, around 10% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Leaking hydrogen is suddenly a big deal from a climate perspective, not only keeping industrial workers in hi-vis vests alive.

But how much could it possibly be leaking? Back to Nature, the most reliable scientific journal in the world, with the paper “First detection of industrial hydrogen emissions using high precision mobile measurements in ambient air.” It looked at a European industrial electrolysis and hydrogen refueling facility, which is to say one that exists in a place where they care a lot about getting leakage down to acceptable levels. What did it say?

“Our emission estimates indicate current loss rates up to 4.2% of the estimated production and storage in these facilities.”

There were a few things in the site they looked at including an electrolysis facility, compressors, storage tanks and refueling points. That’s about 1% per touch point in a good facility.

Unfortunately, a lot of facilities aren’t that good. In the USA, where that kind of engineering and care is a bit rarer, a study of a hydrogen refueling station with an electrolyzer found that losses were between 2% and 10% after years of remediation to bring them down from 30% to 35%. The peer-reviewed paper is “Hydrogen losses in fueling station operation,” and while it’s not in Nature, it’s in a journal with a very respectable impact factor of 9.8. Uninspected hydrogen facilities leak a lot of hydrogen and it takes a lot of effort to bring it down to merely bad levels. At 30% leakage, a ton of hydrogen that gets into a bus would have 12.2 tons of CO2e emissions just from leaked hydrogen.

12.2 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of fuel would not be construed in any court of law to be zero emissions.

And now we get to just moving hydrogen around. It’s a hard molecule to transport. It likes to leak. It’s a really diffuse gas. That means it has to be compressed, liquefied or put into even more energy losing storage solutions. A lot of hydrogen for transportation plays, like Brampton’s or Whistler’s or the hydrogen ferry in Norway, truck in hydrogen from a long way away. 4,500 kilometers in compressed hydrogen tube trucks in the case of Whistler’s bus fleet using diesel trucks. 1,300 kilometers over two days in liquid hydrogen trucks in the case of Norway, with boil off losing 1% to 2% of the hydrogen daily. Not quite as far, but still about 300 kilometers in the case of Mississauga.

A truck or pipeline is an interaction point. Every point where hydrogen is transferred from one thing to another loses perhaps a percentage. If it’s liquefied it loses hydrogen just by sitting there. The US DOE worked out what this was likely to look like for a hydrogen refueling system. What did they find in their technical report on the subject, Boil-off losses along LH2 pathway?

“boil-off losses can vary from 15% of delivered LH2 for a 100 kg/day, 5% at 400 kg/day, and down to less than 2% for stations above 1,800 kg/day”

Making hydrogen in one place and shipping it to another place to put into a vehicle is likely to have an average of 10% losses of hydrogen from manufacturing to being used for energy in a vehicle due to a bunch of touch points and related concerns. That’s really expensive, as hydrogen is never cheap, but the point here is that’s 10% losses of a potent greenhouse gas, one 37 times worse than carbon dioxide over 20 years. 10% losses turns into 3.7 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per ton of hydrogen. Burning diesel emits 3.1 tons of CO2.

3.7 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent for every ton of fuel would not be construed in any court of law to be zero emissions.

One assumes that readers can see where this is going. Winnipeg’s hydrogen greenhouse gas emissions from methanol reformation and the like are 3.2 times worse than diesel. Mississauga’s and Bramptom’s will be only 10% lower than diesel based on current plans, and 60% of diesel in the best case. Every multi-touchpoint use case for hydrogen has high greenhouse gas emissions.

No court of law could hear this evidence and decide anything other than that claims that hydrogen for energy for transportation (or any other energy use case) is zero emissions. Courts wouldn’t accept low emissions and would be hard pressed to agree to even lower emissions.

To be clear, battery electric buses aren’t zero emissions either, but they are the closest thing to them. They travel three to four times as far on the same electricity, assuming that the choice is batteries or making hydrogen and running it through fuel cells. That means that whatever the electricity grams of CO2e/kWh is, it gets multiplied by the kWh per 100 kilometers of the bus.

However, that’s the lowest possible emissions per kilometer in any jurisdiction well-to-wheel. No court, if presented with the basic information in even a barely coherent fashion would consider it not to be lowest possible emissions. It’s the baseline. It’s the bar to get under, or at least approach. And hydrogen doesn’t get remotely close to it. It’s not like it’s double. In the absolute best possible case scenario, Winnipeg doing electrolysis onsite at a transit garage with its very low carbon electricity, it’s 15 or 16 times as bad.

No court of law would consider 15 to 16 times the emissions to be zero emissions.

I’m pretty sure I’ve established that any organization claiming zero emissions for hydrogen transportation is in serious breach of Bill C-59 and its provisions on greenwashing. That means that they are potentially subject to fines of 3% of global revenue or $15 million per breach. It’s hard to reach any other conclusion.

But maybe there’s a loophole. The government, or at least Canada’s Zero Emissions Transit Fund defines a zero emission bus as one that has the potential to emit no greenhouse gases while in operation. That gives a lot of wiggle room. It’s tank to wheel. It’s clearly not the international standard of well-to-wheel. It clearly ignores leakage. It clearly, upon reading, ignores hydrogen’s global warming potential.

It’s pretty clear that the government of Canada won’t be bringing C-59 charges against hydrogen fuel cell chancers. But that doesn’t mean that they are remotely out in the clear.

Bill C-59 introduces a significant shift in advertising regulations, granting private organizations the right to initiate claims for breaches of truth-in-advertising provisions. Previously reserved for federal regulators, this expanded authority aims to bolster accountability in commercial messaging by enabling businesses and non-profits to directly challenge misleading or false advertising practices in court.

As a result, firms that are spouting nonsense about hydrogen today are actually subject to informed and motivated parties bringing suit against them for making the false claim that hydrogen for transportation or even energy in general is zero emissions. As I think I’ve established, there is no court that wouldn’t look at the evidence and agree.

Under the Bill, companies found guilty of greenwashing can face fines of up to 3% of annual global revenues or $10 million CAD for a first offense, increasing to $15 million CAD for repeat violations, along with potential orders for restitution to consumers and cease-and-desist directives. There is no specified limit to the number of violations that can be brought against companies for deceptive marketing practices.

For example, New Flyer had global revenues in 2023 of US$2.7 billion, so could be fined for up to $81 million or CA$116 just with that provision. Ballard had revenues of about US$102 million, so that’s a $3 million fine, but it’s a massive spammer of greenwashing about its products, so consider ten or twenty fines of CA$15 million, potentially a couple of hundred million, more than doubling its $144 million loss for the year (increasing its average of $55 million annually since 2000). Transit organizations exist within the budgets of cities, so don’t have revenues per se, but are still subject to fines.

Even the government isn’t exempt. If it is making false claims, as Canada’s Zero Emission Transit Fund does by claiming hydrogen buses can be zero emissions, they could be found guilty as well.

Canada hasn’t been as litigious as the United States, but it has seen a surge in environmental litigation from individuals and organizations challenging government policies and corporate practices. Notable cases include a youth-led lawsuit against Ontario’s climate policies, claiming inadequate greenhouse gas targets violate constitutional rights, with the Ontario Court of Appeal recently ordering a rehearing. Similarly, environmental and Indigenous groups have legally contested the federal approval of the Bay du Nord offshore oil project, arguing its assessment overlooked climate and marine impacts. The Beaver Lake Cree Nation has also sued federal and provincial governments, alleging oil sands development has infringed on treaty rights and disrupted traditional lands. Meanwhile, Volkswagen faced legal action for violating environmental laws in the emissions scandal, and Suncor is under fire for refinery emissions.

The above article is the basis for an affidavit in court cases on the subject. I would know as one of the more amusing parts of my year is that I’m officially an expert witness in court cases against Toyota proceeding in California related to their false claims related to the Toyota Prius. Those claims have led almost 12,000 Californians to buy a car that can’t be refueled a very large percentage of the time. I’m an expert based on my ongoing assessments of hydrogen transportation, including refueling station failures in the state, where I found that they were being fixed 20% more hours than they were actually pumping hydrogen at a likely annual cost of maintenance somewhere between 10% and 30% of capital cost, unlike the 4% claims usually considered. As part of my involvement, I wrote a 27 page affidavit which is entered into evidence, and will likely be testifying in the first half of next year. That’s a hint for any litigiously inclined groups in Canada.

What this all nets out to is that all of the firms making claims that hydrogen and hydrogen for transportation are zero emissions really need to have their corporate council assess their liability under Bill C-59. If they were smart, they’d remove all references to that from their websites and social media, just as the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, Suncor and Enbridge removed all their greenwashing in the summer time.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy