Emesent’s new Hovermap LHD solution aims to help miners take control of their operations.

Emesent is an automation and digitalisation company that spun out of Australia’s CSIRO in 2018.

Its flagship product, Hovermap, is a simultaneous location and mapping-based (SLAM) light detection and ranging (LiDAR) scanner, enabling autonomous mapping of inaccessible and GPS-denied environments.

The unit can be attached to a drone or a ground robot to provide autonomous navigation and data capture within hazardous, unreachable spaces like stopes or large caves.

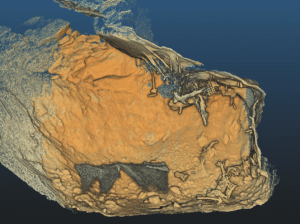

Image: Emesent

Emesent director of product Christian Skinner, and regional sales director of APAC Paul Fenner discussed the company’s latest release, Hovermap LHD, which enhances visibility for load, haul, dump or bogger operations.

How does Hovermap help underground surveying, especially in mining?

Christian Skinner: The output from Hovermap is a high-accuracy, colourised point cloud from which you can derive unique insights about the scanned environment.

It has been designed for speed, versatility and simplicity. Users can quickly attach it to a car, backpack, drone, cage or even a Boston Dynamics Spot and use it to explore and map previously unreachable areas.

Recently, we’ve been expanding our solutions for underground mining to enable faster and better decision-making.

An example is Hovermap LHD. We know mining can expose equipment to hazardous, unpredictable risks that can damage or destroy machinery. This stock or lost equipment can cost tens of thousands of dollars for every hour of lost production – in addition to the recovery costs.

Load, haul, dump (LHD) operations can cost multiple millions of dollars, and there is a long lead time for replacement if that equipment is damaged.

Why have you released Hovermap LHD?

CS: There are many reasons underground incidents occur and more generally why LHDs are not as productive as they should be.

Remote operators often struggle to see the environment they’re in given the limited field of view of the cameras they use, while geotechnical hazards can be precariously sitting within their blind spots.

Even if they can see the rock face, 2D cameras provide limited context of the structural hazards or the implications of removing certain material.

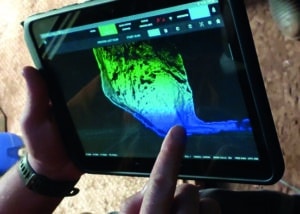

Image: Emesent

In addition to equipment damage from these hazards, production decisions can be delayed by operators waiting for surveyors to be available. This means things like equipment relocation may not be timed optimally based on the remaining volume.

We’ve developed the Hovermap LHD as a simple way for anyone to get a better understanding of the entire stope environment they’re in by helping operators see further with Hovermap’s 300m range and 360º field of view – to give operators a complete map of the stope, even in the dark.

Essentially, Hovermap provides a full three-dimensional visualisation of an area which allows operators, surveyors and geotechs to identify loose rocks, structural hazards and rill angles.

Paul Fenner: It’s easy to look at the LHD mount and think that the solution is based purely on that hardware mount only, but a lot of work has gone into the applicability, the ease of use, and the analysis of data after the fact.

Whether you’re driving or not, and whether you are in the cabin or observing remotely, Hovermap LHD allows you to start a scan remotely and see in the dark where everything is.

What is the potential impact on existing or traditional practices?

CS: Hovermap LHD was designed to be as simple as possible. Anyone can answer their own questions about the operating environment they find themselves in at any time.

The magnetic mount attaches the unit to the roof of the bogger and can be connected to the mine network through the bogger’s M12 connector. The plug-and-play deployment means anyone can create accurate stope scans in minutes.

Users start a scan and drive the equipment into the stope. With Hovermap, unlike terrestrial laser scanning, you do not have to stop the equipment from moving – you scan as the bogger’s moving in and out.

When the scan is complete and you’ve captured sufficient data, you stop the scan and hit review, and the data transfers wirelessly to the remote operator in near real-time.

The unit itself is robust and we’ve completed countless hours of testing to ensure the scan quality isn’t impacted by the rough ground. It can also be mounted to bogger buckets if users need to scan up and into narrow spaces.

Meanwhile, Hovermap’s near real-time visualisation delivers millions of points of actionable detail exceptionally fast. In addition to identifying hazards from a rill angle or suspended rocks, users can see the remaining volume and plan equipment tramming for the end of shift, thus improving productivity.

PF: With Hovermap LHD, the data is being captured by the bogger operator, not a surveyor. The ability to have that data captured and viewable by anyone at the mine adds a lot of value and frees the surveyor to review the data but not have to capture it.

Image: Emesent

The current best practice is that less than 90 seconds of captured data will provide sufficient intel for most of the stope areas. You can get visibility so quickly that you can understand the value that it presents almost immediately.

Our solution provides two things: it gives that immediacy whereby the operator can see what’s going on, but it also delivers a high-resolution, high-density point cloud for a working face; and it does this even in the dark.

Being able to capture that and share that with the remote operating centre or the surface team has helped our customers improve safety by identifying obstacles in risky areas.

Who have you worked with in validating this technology?

PF: This Hovermap LHD solution was developed in partnership with Mining Plus. The advantage for us working with them was in engaging industry experts to look at the real-world applicability and the problems involved in field applications.

Mining Plus has been able to help customers avoid LHD units being stuck. A recent case involved a customer that caught on and pulled down a bit of mesh. This meant that the stope was out of action for many hours while the area was recovered.

One of the things we’ve developed in partnership with Mining Plus is a return-on-investment calculator for different commodities so we can help customers understand how the Hovermap LHD solution benefits them and what the value of optimisation could be through use of this technology.

Image: Emesent

For most copper or gold operations it’s typically one to two hours of lost productivity that Hovermap can prevent, which is often enough to pay for use of the solution. So it’s a very quick return on investment.

During an early test example, we went to a customer with Mining Plus to do some stope scans and they told us that this was an old working with a little bit more ore to get out, but they were happy with the production.

Going in with Hovermap LHD they noticed that there was a rock just above the entrance. It was a six-cubic-metre rock hanging by a roof bolt. Had this fallen on the LHD, it would have been end-of-life for the equipment.

Being able to see these types of things proves value from the get go. And yes, the customer did purchase based on that, but what’s most important is that the operator was able to safely identify the rock. They were then able to do a mini blast to remove the rock to ensure operations continued safely.

CS: There are multiple ways to understand underground mining environments, but we’ve developed this technology so operators themselves have the right information to make decisions quickly and independently.

Hovermap’s versatility means that it can be used by other teams outside of production for things like convergence monitoring, stockpile pick-ups, or shaft scanning – just to name a few.

This feature appeared in the October 2024 issue of Australian Mining.