Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

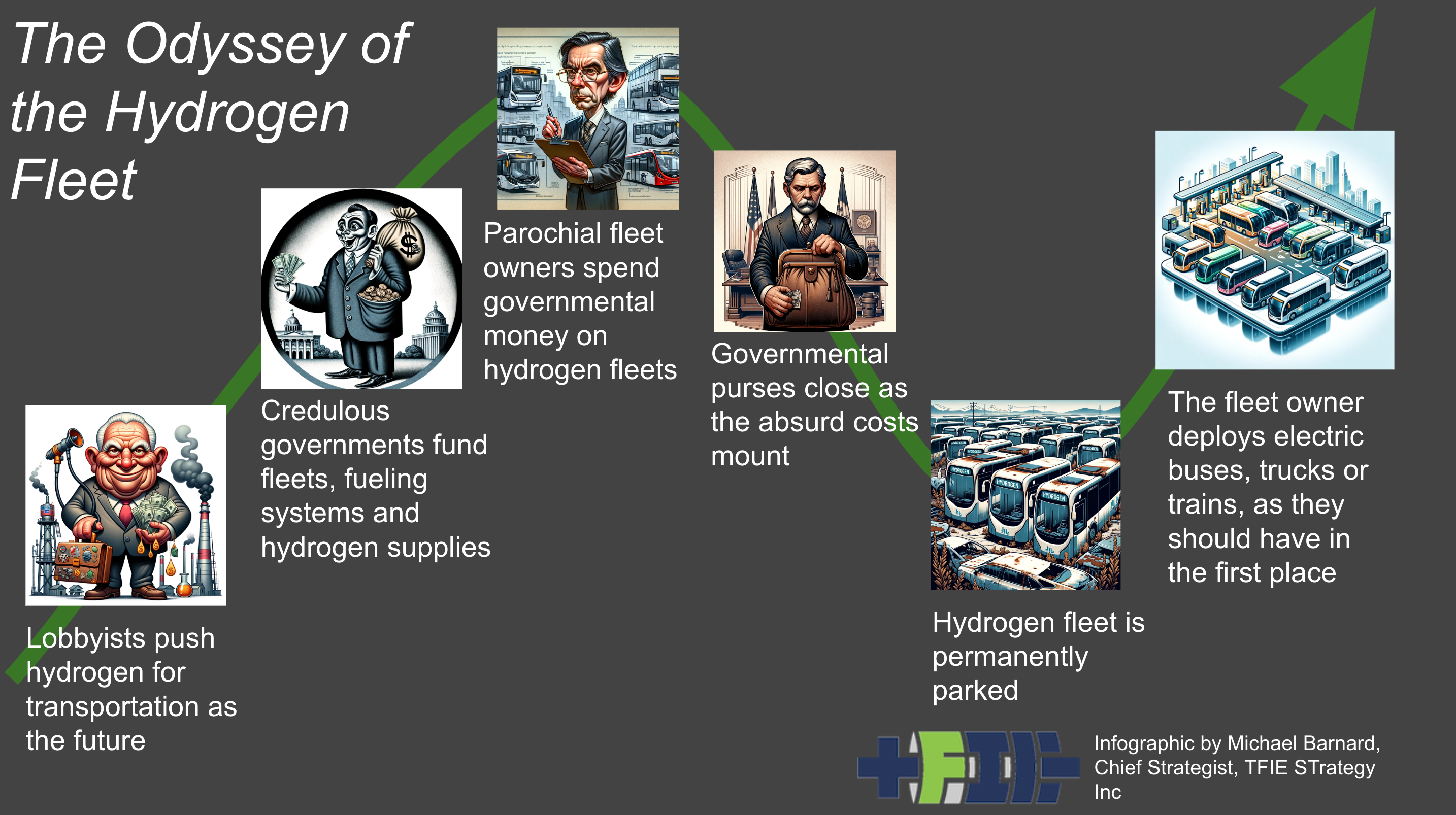

A year ago, I was having fun with the Odyssey of the Hydrogen Fleet, a tragicomedy in six parts. One of the many enactments of this tragicomedy had left Act 5, where the hydrogen fleet is permanently parked. The provincial government of Quebec quietly returned roughly 50 fuel cell cars they’d leased to Toyota.

I had assumed that like many pilot initiatives, the results would never be made public, but today a Quebec correspondent shared the report with me. It doesn’t look good for hydrogen light vehicles, but that’s unsurprising.

Let’s start with a reminder of the tragicomedy’s parts. In act one, oil-slicked lobbyists push for hydrogen transportation funding and pilots. In Act 2, well-intentioned but STEM- and economics-illiterate government apparatchiks are seduced and unlock big pots of money. Act 3 sees a fleet operator, cash-strapped, salivating over the big pots of money and buying a hydrogen fleet and attendant expensive pumping station and hydrogen with it.

Act 4 sees a wiser governmental head look at the extraordinary costs and poor results and move the pots of money into a more suitable program. In the absence of further funding, Act 5 sees the fleet operator dealing with the return of fleet or perhaps just scrapping it, and figuring out what, usually nothing, to do with the hydrogen refueling infrastructure. Act 5 sees the return of rationality with an electric fleet, what should have been purchased in the first place.

In 2019, the Quebec government started down this journey. In December of 2023, they quietly returned the 45 Toyota Mirai to that quixotic tilter at hydrogen-powered windmills, and did the same with the sole Hyundai Nexo.

Initial data on the program indicated that it was very expensive. The refueling station in Quebec City, where the entire fleet was based, was capable of refueling a single vehicle at a time and cost CA$5.2 million. Over CA$1 million more was spent on leases for the vehicles, for the most part. The cost of the hydrogen was unstated at the time, but data from the rest of the world shows that hydrogen at retail rates at pumps costs from $15 to $35 per kilogram. More on that later, but let’s talk about fleet usage statistics first, because they are eye-popping.

One thing is very clear: the hydrogen cars weren’t popular with Quebec governmental employees. After they had some time with the cars, they voted with their accelerator pedal-pushing feet to drive other governmental vehicles instead, or maybe just walk or bike. I don’t have statistical data on driver preference in fleets with mixed electric and internal combustion vehicles, but the anecdotal data is rich that drivers vastly prefer EVs to ICE cars and trucks. That’s what Pepsi found with its Tesla Semis and that’s what others found. In one case, to avoid conflict, they had to put hour-limits on drivers getting the EVs so that others could drive them too.

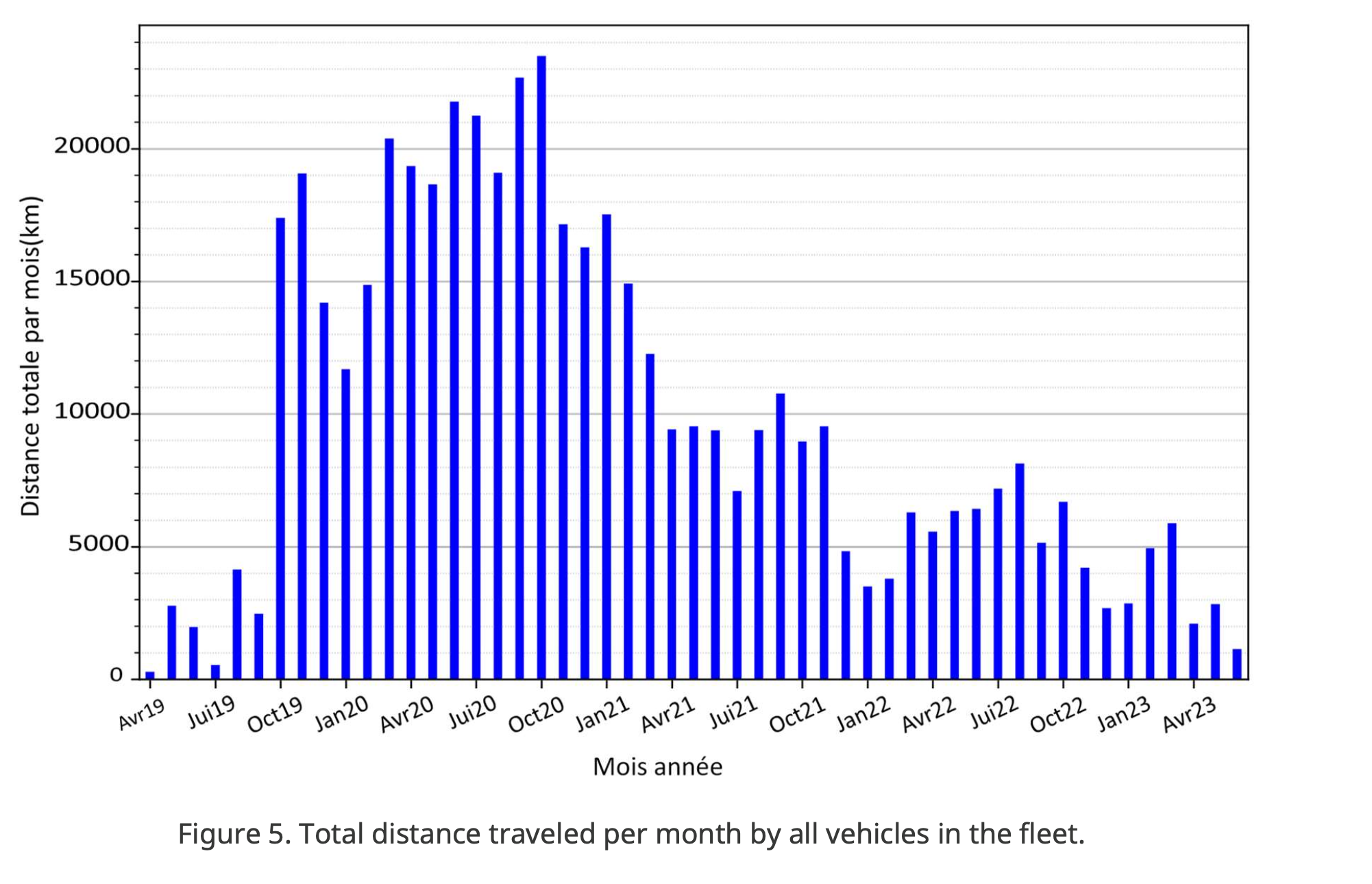

Even at that, some statistical assessments start to show even more starkly that there’s a big problem here. The report indicates that the fleet traveled a shade under 500,000 kilometers in four years. For 46 vehicles, that turns into only 2,700 kilometers per year on average. US governmental fleet data shows that its vehicles average 16,000 to 24,000 kilometers per year of driving, which is to say that they drive about as much as the average American. Because Canada’s development was just as sprawl-based as the USA’s, that’s a reasonable comparison.

This fleet was driven about 13% as much as similar fleets. Some of the vehicles were so little used that they had to create a category for them and exclude them from a lot of statistics, otherwise things would have looked even wonkier. What was the constraint that they used? A car had to be driven more than 200 kilometers in a quarter to be included. That’s two kilometers a day.

There was another tantalizing tidbit from the report on cold weather performance. That’s a trope that’s thrown at battery-electric vehicles constantly by fuel cell and internal combustion proponents.

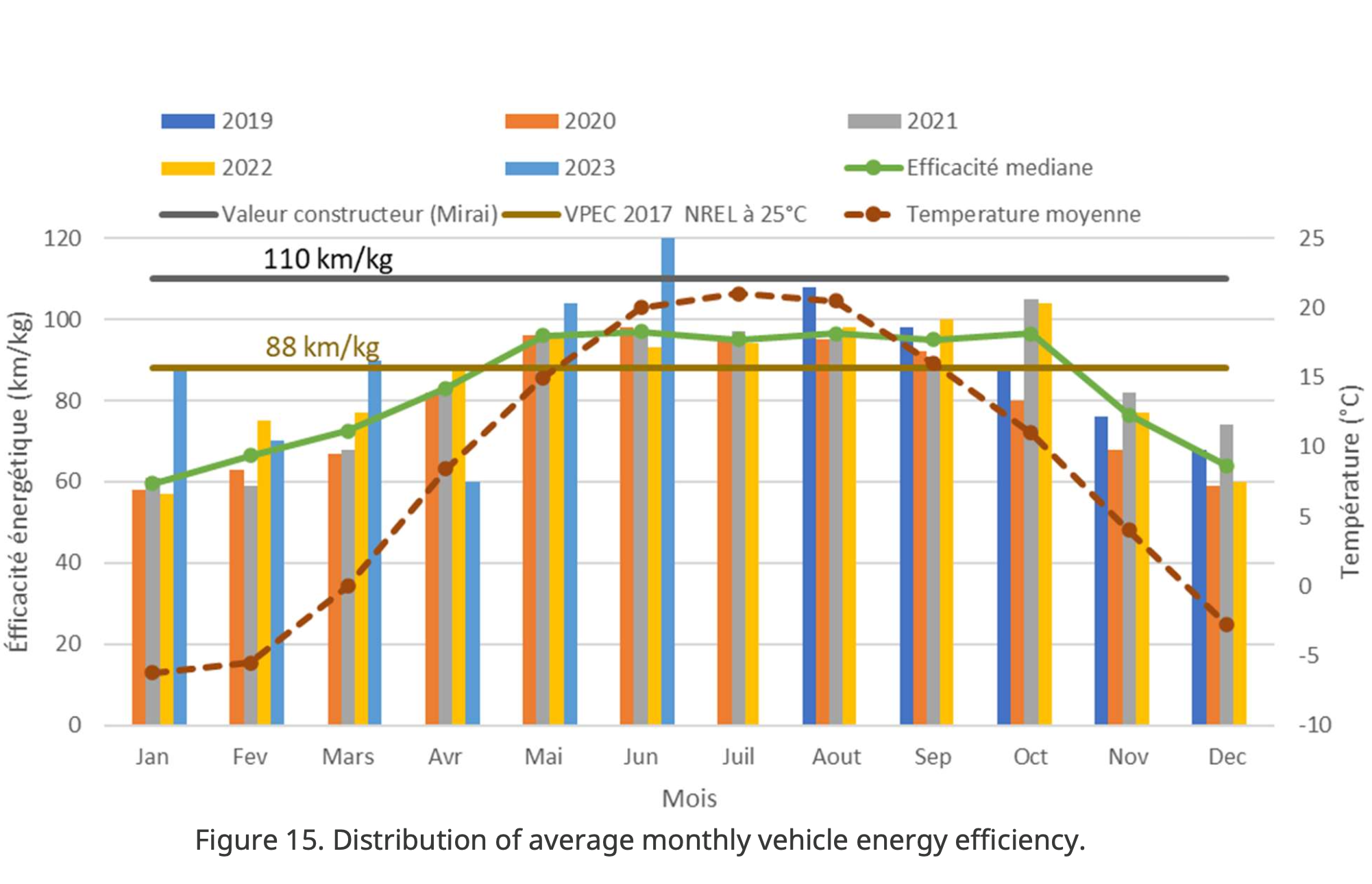

This rather busy chart basically says that colder temperatures saw plummeting fuel call vehicle efficiency. Per the report:

“The vehicles’ performance revealed an average energy efficiency that varied according to the seasons and temperatures, with optimal performance reaching 95 km/kg of hydrogen in summer compared to approximately 70 km/kg of hydrogen on average in winter.”

That’s a 27% efficiency drop. That’s in the same ballpark as battery-electric cars, hence so much for that differentiator. Internal combustion cars see lower efficiency losses, 10% to 20%, but remember that’s on their incredibly inefficient and 100% emitting drivetrains.

Around the same time as the Odyssey, I was working with a Swedish road transportation decarbonization study for Europe. That led me assess the outages of hydrogen refueling stations in California in their most used, most mature six-month period before reporting on them was stopped. I found that on average they were out of service more than they were actually dispensing hydrogen — a lot more. Total hydrogen dispensing hours in those six months was about 9,700 hours, while total time being maintained was 11,700 hours, which is 2,000 hours more. As with the Quebec fleet vehicles, part of this is that there just aren’t that many hydrogen vehicles, so stations sit empty most of the time.

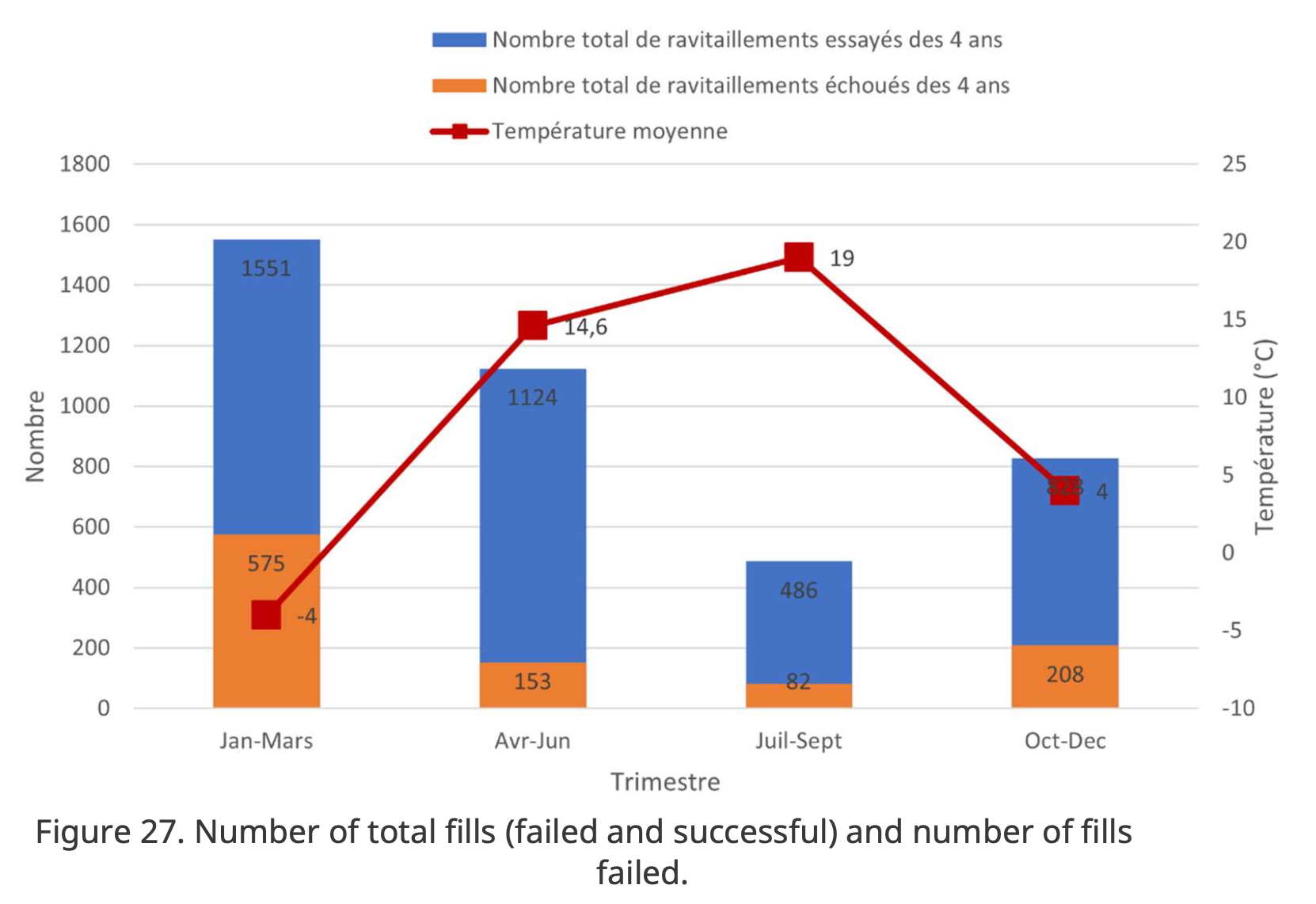

The total height of the bar in the chart above is the average number of refuelings attempted each week in the quarters. The blue bar shows successful refuelings. The orange bar shows failed refuelings. In January to March over the four years, the average attempt to refuel one of the hydrogen cars failed more than one in three times, requiring an attempt to refuel at another time. The ‘good’ quarters still saw failures to fill one in six times.

This isn’t some neglected electric car charging point in the back of a dusty lot with the wrong charging card or connector. This is the only hydrogen refueling pump in Quebec and it’s on the lot of a gas station that’s staffed and pumping gas all day. It had the 45 Mirai, the one Nexo, and the roughly 20 other hydrogen fuel cell cars in the city.

This pumping station was built specifically for the governmental fleet, and the other 20 owners, whether private or commercial, were suckered in with the government, something that Mirai owners in California have told me makes them remarkably angry. Try to do the right thing, something your elected officials assure you is the right thing, only to find out that you’ve been suckered into an unreliable dead end.

So yes, in addition to having pretty much exactly the same loss of range as electric cars, hydrogen cars fail to get any range at pumps when it’s cold.

You can see this in the declining usage data from the month-by-month kilometers chart above. There are dips in kilometers driven in the winter time that are visible. The people who had these cars available learned that it was better to figure out another way to get around rather than to try and use them when it was cold. And note, this is Quebec City, whose nicknames include the City of Snow and the Capital of Winter.

Another chart in the report provides the hours of station unavailability by component that failed. The total hours add up just over 11,000 hours of downtime for the four years. How much is that? Well, that’s almost a third of the total hours in four years. I’m pretty sure that a few informal chats sprang up to let people in the same ministries know that the station was down again and to avoid using the Mirais if they weren’t full already. The ones who drove more probably had Quebec’s Centre de gestion de l’équipement roulant (CGER) do the refueling after hours, a service that the organization provides for some governmental fleets as required. The person being paid to drive cars to non-working refueling stations probably doesn’t care as much that the station is dead and is willing to hang around being paid while it gets fixed.

Then there’s the cost of all of this. The report is rather absurdly quiet on this. I’ve never seen a fleet operator report that doesn’t care deeply about total cost of ownership, and there is exactly zero mention of this. I assume that an earlier version of the report was transparent about it, then it went up to the level below the Sous-ministre adjoint (assistant deputy minister), where someone broke out in a cold sweat and realized how much money they had wasted, and how embarrassing it would be given how entirely predictable it was.

The only reference to costs in the document are an estimation of the cost of the electricity required to manufacture the hydrogen consumed over the course of the four years. At Quebec commercial rates, it was assumed to be about CA$9.10 per kilogram, with the electricity being used at the refueling station to electrolyze water and stored in tanks at 350 and 850 bar. Of course, 850 bar requires about 5 kWh of electricity for compression of a kilogram, so that’s another 10% on that cost.

As an aside, the only good news story in this entire debacle is that Quebec’s grid electricity is now at 1.2 grams CO2e per kWh, about the best in the world. As a result, each kilogram of hydrogen had a carbon intensity of about 0.07 kg CO2e, which is actually green hydrogen. This is worth calling out, as it’s incredibly rare for actually green hydrogen or even electrolyzed hydrogen from a dirtier grid being used in these hydrogen trials. What green hydrogen is being pumped into Barcelona’s hydrogen buses, when they are operating at all, is made from Spanish electricity which averages 175 grams CO2e, for a carbon debt for hydrogen of almost 10 kg CO2e per kg H2. Yes, that’s worse than diesel buses. The Plug Power electrolyzer at the Amazon’s Colorado distribution center for its fuel cell forklifts is even worse in terms of carbon intensity.

The energy in a kilogram of hydrogen is equal to a US gallon, that completely nonsensical measure used nowhere else in the world, and immaterial in Canada, of course. As a little historical note, the size of the US gallon originates from the English wine gallon, which was defined in 1707 during the reign of Queen Anne. The English wine gallon was established as 231 cubic inches, a size derived from the volume of a cylinder 7 inches in diameter and 6 inches in height. This volume was used to measure wine and other liquids and eventually became the basis for the US gallon. (Yes, I continue to be bemused that the USA clings to the skirts of the British Empire in this way.)

In units that the rest of the world uses, a kilogram of hydrogen has the energy of 3.785 liters of gasoline. A fuel cell drivetrain is more efficient than the incredibly inefficient internal combustion drivetrain found in cars and light vehicles historically. As a result, the actual forward motion per kilogram is about double what that suggests. Let’s call it equivalent to 8 liters of gasoline. Right now, the cost of a liter of gasoline in Quebec City is about CA$1.50, so on a forward movement basis, a reasonable price at the pump would be around CA$12.00 per kg for fleet operating cost parity.

That would seem to suggest that the CA$9.1 per kilogram cost of manufacturing the hydrogen was a lot less than the cost of gasoline for an equivalent fleet, although the report doesn’t go so far as to say that explicitly. The aforementioned loss of efficiency in the winter by itself meant winter costs of fuel were above gasoline costs, not to mention far above the costs of just using the electricity in electric cars.

But the CA$5.2 million spent on the station was mostly funded by the government directly, with CA$2.9 million from Transition énergétique Québec (TEQ) and another CA$1 million from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), for CA$3.9 million, a full three-quarters of the cost. Apparently, Air Liquide, a global leader in gases and related technologies and services, built and operated it in partnership with the government of Quebec under the auspices of the non-profit umbrella advocacy organization Hydrogène Québec. Presumably Air Liquide ponied up most of the CA$1.3 million in the vain hope that they would be able to hook the government on hydrogen in perpetuity, so it was a good marketing expenditure.

But let’s pretend that the CA$3.9 million was amortized across the governmental use of hydrogen, with a 40% uplift for the small number of private vehicles. The total consumption of hydrogen in the governmental fleet was just over 6,100 kilograms. If you’re thinking that CA$3.9 million is a quite large number and 6,100 is a quite small number, your mathematical insights would be spot on.

Assuming the uplift for the other 20 or so hydrogen vehicles in Quebec City, that’s around CA$500 per kilogram of hydrogen over the four years. Suddenly, that CA$9.10 doesn’t look nearly as good. The CA$1.3 million from Air Liquide was about CA$150 per kilogram, so I’m pretty sure that they no longer consider it a worthwhile marketing line item.

Then, of course, there’s the cost of all of the people trying to refuel and being unable to refuel because the station was out of service a third of the time. Then there’s the cost of fixing the station all the times that it broke. Unlike California’s fuel cell buses, which are out of service 50% more of the time than their diesel buses, the Mirais were fairly reliable, partly because they were barely used, and of course they gave them all back last December, so have no ongoing liabilities on their books.

The Quebec hydrogen light vehicle four-year program shouldn’t have been run. Results were available from fleets globally that made it clear it would be an expensive failure. The effective costs of CA$500 per kilogram of hydrogen, equivalent to about CA$63.00 per liter of gasoline, were entirely predictable. The report is an exercise in face-saving, containing lots of details, avoiding lots of more pertinent details like context, and refusing to draw the obvious conclusions, that hydrogen ground vehicles aren’t remotely fit for purpose.

The only good news is that it’s over and unlikely to be repeated. At least, in Quebec. The Odyssey of the Hydrogen fleet keeps being restaged in cities around the world, each new venue refusing to learn the lessons of every other venue over the last quarter century, that you can’t turn a profit on this tragicomedy.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy