If you are reading this, your life has been touched by John Goodenough, the world-renowned scientist who passed away yesterday at the age of 100. Why do we say that? Because John Goodenough was directly and intimately involved in the development of wireless communications and lithium-ion batteries. If you use the internet or have a smartphone or a laptop computer, it is thanks in large measure to his efforts.

That statement needs some explanation. Science is a collaborative effort. Goodenough did not invent wireless communications or the lithium-ion battery on his own, but he was a leader, someone who inspired others to keep reaching for achievements that others thought were impossible. There are obituaries for him today from all around the world, including the New York Times. For 37 years, Goodenough was a professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering at the University of Texas Austin. And so it is fitting to celebrate his extraordinary lifetime by quoting from the official final tribute to him published by UT.

“John’s legacy as a brilliant scientist is immeasurable — his discoveries improved the lives of billions of people around the world,” said UT Austin President Jay Hartzell. “He was a leader at the cutting edge of scientific research throughout the many decades of his career, and he never ceased searching for innovative energy-storage solutions. John’s work and commitment to our mission are the ultimate reflection of our aspiration as Longhorns — that what starts here changes the world — and he will be greatly missed among our UT community.”

Goodenough served as a faculty member in the Cockrell School of Engineering for 37 years, holding the Virginia H. Cockrell Centennial Chair of Engineering and faculty positions in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Chandra Family Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. Throughout his tenure, his research continued to focus on battery materials and address fundamental solid-state science and engineering problems to create the next generation of rechargeable batteries.

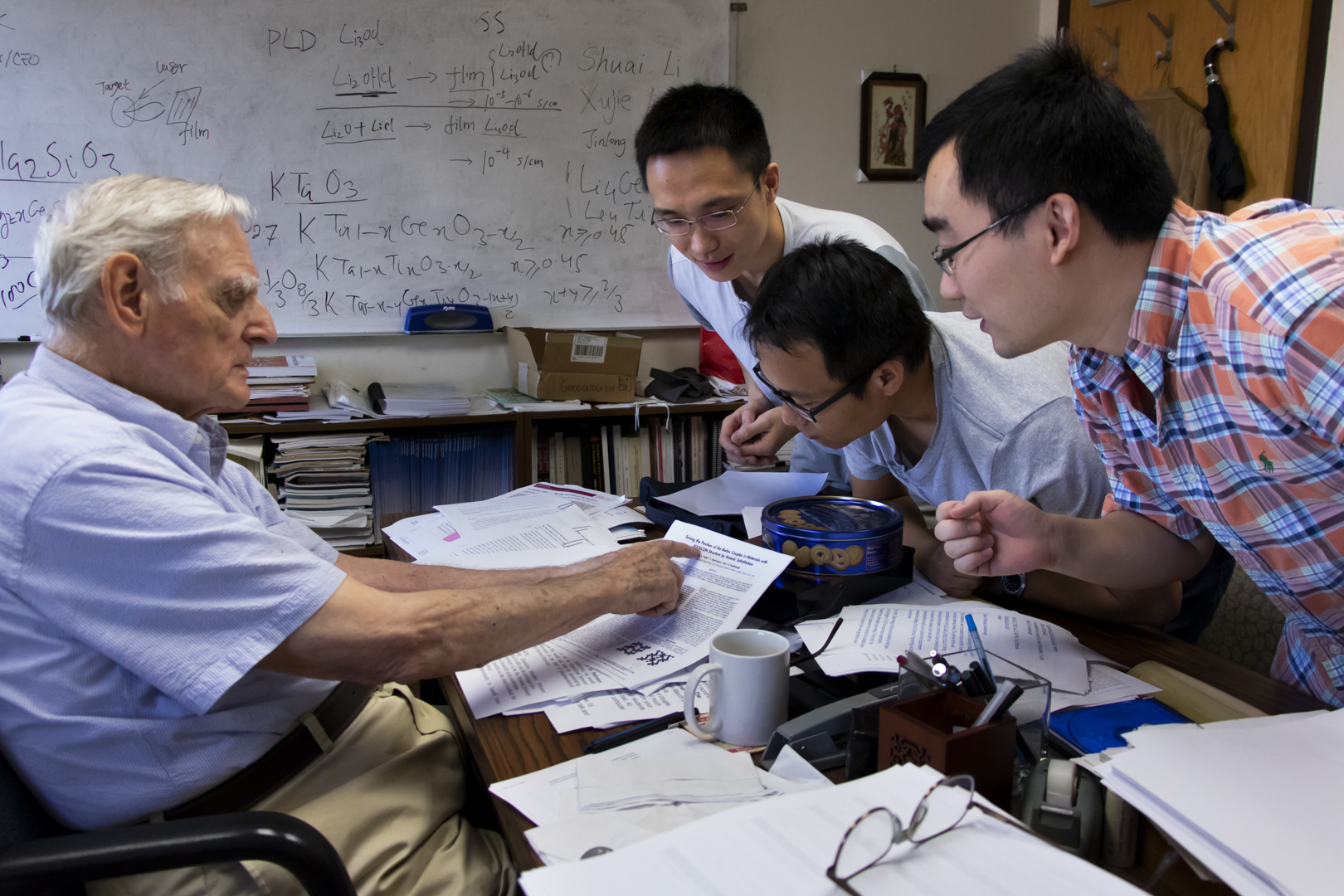

“Not only was John a tremendous researcher, he was also a beloved and highly regarded teacher. He took great pride in being a mentor to many graduate students and faculty members who benefitted from his wisdom and encouragement,” said Provost Sharon L. Wood. “The world has lost an incredible mind and generous spirit. He will be truly missed among the scientific and engineering community, but he leaves a lasting legacy that will inspire generations of future innovators and researchers. I am honored to have known and worked with John.”

Goodenough identified and developed the critical cathode materials that provided the high-energy density needed to power electronics such as mobile phones, laptops and tablets, as well as electric and hybrid vehicles. In 1979, he and his research team found that by using lithium cobalt oxide as the cathode of a lithium ion rechargeable battery, it would be possible to achieve a high density of stored energy with an anode other than metallic lithium. This discovery led to the development of carbon-based materials that allow for the use of stable and manageable negative electrodes in lithium ion batteries.

“John was simply an amazing person — a truly great researcher, teacher, mentor and innovator,” said Roger Bonnecaze, dean of the Cockrell School. “His joy and care in all he did, and that remarkable laugh, were infectious and inspiring. What an impactful life he led!”

He came to UT Austin in 1986, setting out to develop the next battery breakthrough and educate the next battery innovators. In 1991, Sony Corp. commercialized the lithium ion battery, for which Goodenough provided the foundation for a prototype. In 1996, a safer and more environmentally friendly cathode material was discovered in his research group, and, in 2020, a Canadian hydroelectric power company acquired the patents for this latest battery.

“John’s seven decades of dedication to science and technology dramatically altered our lifestyle, and it was truly a privilege to get to work with him for so many years,” said Ram Manthiram, professor in the Cockrell School who was a longtime friend and associate of Goodenough’s and joined him at UT in the 1980s. Manthiram, a battery pioneer in his own right, delivered the Nobel lecture in Stockholm on behalf of Goodenough. “John was one of the greatest minds of our time and is an inspiration. He was a good listener with love and respect for everyone. I will always cherish our time together, and we will continue to build on the foundation John established.”

Goodenough’s quick wit and infectious laugh were defining characteristics that influenced the level of fame he received. That laugh could be heard reverberating through UT engineering buildings — you knew when Goodenough was on your floor, and you couldn’t help but smile at the thought of running into him.

He was still coming into work well into his 90s. For him, there was no reason not to. “Don’t retire too early!” Goodenough told the Nobel Foundation and others. It was advice he frequently gave and certainly followed.

Image credit: Adrienne Lee, University of Texas

What a remarkable life! And yet there was little indication early in his life that he would become such an internationally renowned scientist. According to the New York Times, Goodenough kept a tapestry of the Last Supper on the wall of his laboratory. He found its depiction of the Apostles in fervent conversation — like scientists disputing a theory — reminded him of a divine power that had opened doors for him in a life that had begun with little promise.

He was the unwanted child of an agnostic Yale University professor of religion and a mother with whom he never bonded. He grew up lonely and dyslexic in an emotionally distant household. He was sent to a private boarding school at 12 and rarely heard from his parents thereafter.

With patience, counseling, and intense struggles for self-improvement, he overcame his reading disabilities. He studied Latin and Greek at Groton and mastered mathematics at Yale, meteorology in the Army Air Forces during World War II, and physics under Clarence Zener, Edward Teller, and Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago, where he earned a doctorate in 1952, the Times reports.

At the MIT Lincoln Laboratory in the 1950s and 1960s, he was a member of teams that helped lay the groundwork for random access memory (RAM) in computers and developed plans for the nation’s first air defense system. In 1976, as federal funding for his MIT work ended, he moved to Oxford to teach and manage a chemistry lab, where he began his research on batteries.

That research led to the first prototype of a lithium-ion battery. The story at that point takes a dark turn, as it appears one of his colleagues spirited the research to Japan, depriving Goodenough of the opportunity to profit financially from the new technology. Today, billions of dollars are involved in the quest to commercialize lithium-ion battery technology, but Goodenough never saw a dime. The UT obituary makes passing reference to the fact that Sony was the first to commercialize the lithium-ion battery, but that rather glosses over the details of the story.

In 2019, John Goodenough shared the Nobel Prize for his work on lithium-ion battery technology. Still, outside the scientific community, he remained relatively unknown, even though his life’s work touched virtually every person on Earth. So thank you, John Goodenough. Humanity is forever in your debt. Godspeed.

Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica, want to advertise, or want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Former Tesla Battery Expert Leading Lyten Into New Lithium-Sulfur Battery Era — Podcast:

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it! We just don’t like paywalls, and so we’ve decided to ditch ours. Unfortunately, the media business is still a tough, cut-throat business with tiny margins. It’s a never-ending Olympic challenge to stay above water or even perhaps — gasp — grow. So …