This Old House has to do some renovating first

By Geoffrey Cann

With Apple’s new Vision Pro hitting the news, and changing the perception of computing to include a spatial dimension, it’s worth reflecting on where and how this clever new technology could be used in oil and gas.

I tend to keep an eye on Apple’s product announcements because Apple has a history of inventing technologies that break new ground (the iPod, the iPhone, iPad, the App Store, Apple Watch), Apple’s market cap is so big, and I’ve personally gone all in on Mac for my day to day.

It wasn’t always this way. I count myself among the very first Microsoft customers. My initial paid-for job in university (aside from manual labour) in 1981 involved coding a data entry system for credit card fraud records for the Canadian Bankers’ Association (a club of big Canadian banks), using a brand new computer called the IBM PC, and software from a start up called Microsoft. In the following 37 years, I lived exclusively within the Microsoft world. In 2018, I moved over to the Apple family so that I could stop being my own help desk trying to solve integration problems in the Microsoft world.

As a tease about the future, spatial audio arrived a couple of years ago on Apple’s airpods and Music services. I flicked it on without thinking about it, and right away noticed the difference in audio experience.

Apple’s latest product, spatial computing, is long on nifty and clever, but short on a must have new feature worth paying the price of a high end Mac Studio with a two hour battery life.

- Watch a movie in surround vision? Ok.

- Use your hands to manipulate apps instead of a mouse? Fine.

- Thrown an app into space and open it? Sure.

- Do a video call? Um.

During the launch, there was no obvious killer app for the masses, and nothing that compelling for business, and in particular the energy industry.

For example, it’s highly unlikely that Apple has made the Vision Pro intrinsically safe. A safe device has been designed and built so that it is incapable of triggering combustion or igniting any gasses, powders or liquids. Apple doesn’t make any devices to this standard, and the company doesn’t publish its product specs that would allow others to assess its safety profile.

As a result, the Vision Pro won’t be permitted anywhere near live upstream production sites, off shore platforms or midstream operations facilities. Even downstream fuel stations are iffy, particularly around the fuel pumps.

Still, there are a lot of workers in oil and gas that are toiling away in offices. Perhaps the Vision Pro will suite the needs of the intellectual worker.

Most of the Apple product suite is for individuals—phones, tablets, laptops, desktop computers, music players, speakers, TV. Apple also publishes a huge range of highly integrated software products (Keynote, Pages, Numbers, iMovie, Books) across multiple platforms (iPhone, iPad, Watch, Mac), which reinforce Apple’s focus on people and how they use technology to better their lives, including intellectual workers.

So far, spatial computing, as I see it, enables the individual to engage with traditional computing assets (apps) and digital things (data, pictures, video, audio) in a virtual space. In other words, it moves our current world of computing off the desktop, laptop, or the little pane of glass. From there, the assets and things, even people, can be in space, free floating in front of your eyes (or augmented reality), or on some other surface, either real or virtual. People are increasingly represented digitally using video conferencing tools like Zoom. Are you really interacting with Tony from Procurement or a virtual version of Tony?

It’s all very people centric, and of course there are 9 billion possible customers out there. At $4k per spatial computer, it’s an addressable market of $36 trillion (gasp), just for the hardware. The App Store will generate another steady tsunami of cash as Apple captures 30% of all IP sold through its platform to run on its hardware.

Apple clearly has staked out the human-to-human world of technology, and has largely left the human-to-machine and machine-to-machine worlds for others to sort out. Apple itself has only a few product examples where its technology is aimed at controlling things in the environment. HomeKit is one. CarPlay interacts with car consoles, but that’s not the same as how a battery electric car provides for self driving capabilities.

The energy world is not really about people. In fact, we spend enormous amounts of treasure trying to keep people from coming into contact with our products (fuels, electricity). For consumers, energy is just there, in the background, behind a light switch, or in response to a quarter turn of a key in an ignition. For energy suppliers, our world features many more machines, with complex interfaces, more regulations, more safety. But our house is definitely spatial:

- Ours is a network or linear business which futures hundreds or thousands of far-flung assets connected up via some kind of network (pipelines but also rail, ocean shipping).

- Energy is a scale business, and our real assets are physically huge. Using Google Earth, visit Ras Laffan, Qatar, to grasp the scale of the assets.

- Energy infrastructure is spatial even under water, on ocean floors, beyond Google’s cameras.

- Our reserves underground are orders of magnitude larger than even those we can see on the surface. The geologic models that characterize the subsurface are much like models for outer space.

- The digital versions of our assets (our digital twins) are equally daunting to grasp.

- Many of the apps our intellectual workers use come equipped with a map-based or geographically oriented user interface to help workers visualize the data more easily.

- Our industry struggles to reduce the knowledge it has about its business into human-sized digestible chunks.

The one significant ‘people’ issue that oil and gas faces is a looming shortage of qualified people interested in energy. Our industry is already experiencing a rapid shift in resource availability, as young people elect careers elsewhere, and experienced resources retire. This gap in capacity (numbers) and capability (knowhow and experience) needs to be overcome by making existing resources more efficient and productive. Anything that can help cross this divide will be most welcome.

It stands to reason that spatial computing as an idea must be applicable to a huge asset intense industry that operates at scale, intimately integrated with the physical world, and highly dependent on a shrinking talent pool.

Here are some examples where intellectual work could be reimagined with spatial computing.

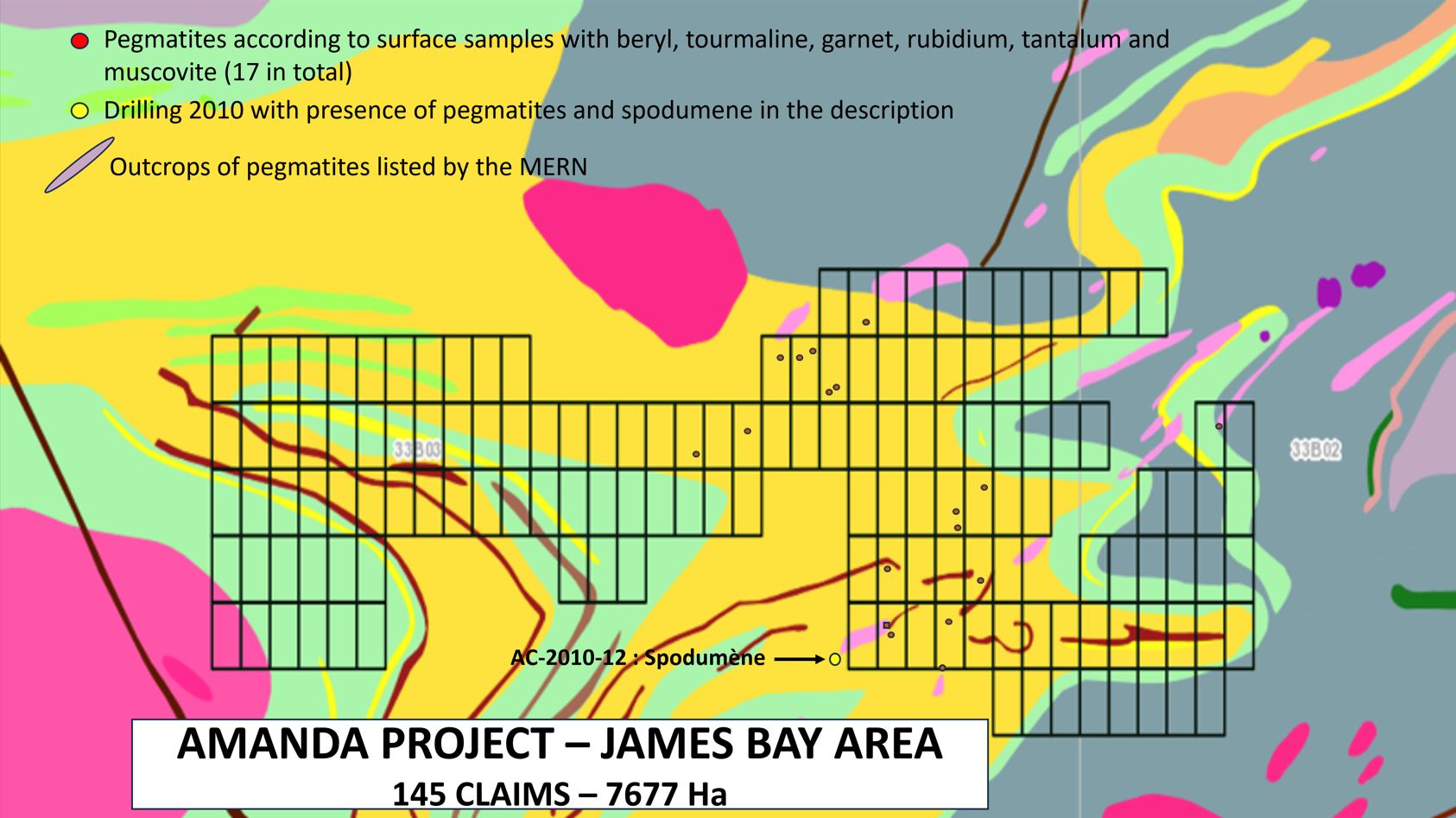

Exploration

Geological and geophysical data is already in three dimensions, and spatial computing could assist exploration and production engineers engage more fully with that data, regardless of where they live. $3500 is less than the price of a return trip for an engineer in Houston to visit Aramco in Riyadh. Expect gains in improved drilling planning, reservoir analysis, and well completion.

Design

Engineers already use three dimensional modelling tools to design new infrastructure. Design work could move in part to a spatial computing structure. Related to design are walk throughs, where teams of engineers review designs and sort out interface concerns between disciplines (hot piping too close to human passage), or safety (gauges at height instead of at ground level). Such reviews could be done with teams in different locations at the same time.

Procurement

Energy infrastructure is a complex sale, and anything that can reduce the friction in obtaining permits, regulatory approval, and stakeholder support is welcome. Digital representations of these industrial assets are very valuable even at these early stages of procurement, and better tools to help explain how energy assets will interact with the real world would be welcome.

Supply Chain

Fabricators already experimented with augmented reality tools in fab shops during the pandemic, when quality assurance inspectors were unable to travel to the fabricator to supervise builds. Fab shops may allow intrinsically unsafe devices onto the shop floor, and the power of interacting with an asset under build with the planned design superimposed is transformative.

Safety

Armed with interactive digital models of infrastructure, safety professionals can simulate various emergency situations, and train safety personnel in virtual environments. Vision Pro could help create a hyper realistic disaster game lasting a couple of hours to test out the spatial aspects of incidents for more efficient and effective actions.

Other possibilities

- Training new workers on large assets, replacing experienced hands with technology

- Work planning for turn arounds, to help accelerate turn around execution by increasingly less experienced workers

- Trialing complex interventions on equipment, helping junior engineers perform like pros

- Monitoring remote assets like unmanned offshore platforms or dill sites virtually, creating leverage for remote operators.

None of these really qualify as the killer app, the multi-billion dollar win.

In any case, the Vision Pro sales material makes it all look deceptively easy, but Apple has a strict architecture that makes integration feel very normal. Our past compute architectural choices in oil and gas constrain us. Even small scale energy businesses operate hundreds of incompatible apps that we struggle to stitch together. Our data is balkanized into thousands of discrete data sets with weird names, limited search, and uncertain provenance and quality. Our equipment portfolio is vast, and dates back decades in some cases. Our suppliers perpetuate the status quo with moats, walled gardens, and slow-walking digitalization.

Our old house isn’t ready for this. We have a huge technology debt in the form of a major renovation we must pay before we can really leverage this technology, and embrace the next killer app, when and if it arrives.

I was delivering training this past week to an integrated oil and gas enterprise and one of the students asked a question that neatly capsulized the challenge of our industry to embrace modern technology. “Some of our oil production assets date back to the 1940s. Do you have any suggestions about how we introduce modern digital innovations to this old infrastructure?” Indeed. Vision Pro and all its cleverness look great until they meet our house from the 1940s, and last renovated in the 1990s.

Artwork is by Geoffrey Cann, and cranked out on an iPad using Procreate.

Share This: