The retail portion of the fuel chain is the most visible to the general public and likely the most complex to navigate.

Who Comes Up With Retail Gasoline Prices?

If you ask the average person who sets the price of gasoline at their local station, they might tell you that the station owner slaps the price tag on the pump – while shaking their head at how much their fuel bill eats into their monthly budget.

But that’s not really the case.

A station wants their market share to be as big as possible for their location, so it’s about maximizing their gallons with the highest possible profit against their competitors.

It’s a complex process to make sure the station’s price matches the “value” the brand offers in a market in terms of customer perception, all while making sure the station sells as many gallons as possible and makes as much money on those gallons as possible.

Elasticity of demand comes into play here, as some stations have very elastic volumes (meaning if they lower their price, they increase their gallons), while many stations have very little elasticity, so lowering their price against competition doesn’t actually gain them gallons, therefore just costing themselves profits. It’s VERY complicated.

Competition on the Street

Remember how we said earlier that spot and rack prices could change daily?

That’s not the case with retail. Most retailers change their prices 3-4 times per week. Very few do dynamic pricing where they change their prices more than once a day, unless markets are going haywire.

Retailers are trying to strike a balance with margin and volumes to maximize their profits, while keeping their brand positioned how they want it to be for customers compared to other competitor stations nearby.

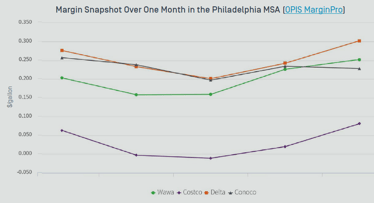

The retailer always must be mindful of what his competition is charging, especially if he or she is competing against a “hypermarketer.”

A hypermarketer is someone like a Wawa, or a Costco, who sells fuel to get the customer into the big-box store to buy items other than gasoline. Many times, those hypermarketers give up their margin for the sake of increased inside sales.

As you can see, competition is fierce and owners need to be aware of what their competitors are charging, so they can attract repeat business and sell more fuel.

Do Brands Operate Retail Stations Anymore?

Two decades ago, most U.S. gasoline stations were branded to a major flag – like Exxon, Mobil, Chevron, Shell or Texaco. Chances are, you probably even had a brand-specific gas card.

But, in just the past 15 years, the retail marketplace transformed. That gas card is probably long gone from your wallet, replaced by Visa, AMEX and debit cards. And that’s just one of many changes…

But, in just the past 15 years, the retail marketplace transformed. That gas card is probably long gone from your wallet, replaced by Visa, AMEX and debit cards. And that’s just one of many changes…

The majors consolidated among each other to create larger conglomerates, a.k.a.

“Super Oil Companies.”

A huge portion of the gasoline stations that used to be owned by popular fuel brands

got sold off. The playing field got a lot smaller – and much more competitive.

Adding to the competitive landscape are those hypermarketers we just talked about. Wawa, Costco, WalMart, Sam’s Club, Safeway and BJ’s Wholesale, just to name a few, started selling fuel.

Also, we can’t forget that the majors have decided that they don’t love owning the “real estate.” They don’t want the headache of operating service stations – staffing and maintaining them. They’d rather focus on supplying fuel through their branded distributors or focusing more time on oil exploration. As a result, huge chunks of the stations in the U.S. have been sold off in the last several years.

The Company-Operated Station

Who Are They?

Owned and operated by a major refiner, the company-run station was until recently a diminishing breed in the U.S. as majors focused on other areas of their business. But lately majors are exploring a re-entry into retail so that they have guaranteed places to sell their supply as demand diminishes slowly over time due to the energy transition and sustainability initiatives.

In the case of the “company-op,” the refiner owns the land, pumps and any above-ground

structures (such as a carwash or convenience stores). The oil company hires the staff to run the

retail site.

How Do They Buy Their Fuel?

The refiner supplies the station directly via its own delivery network and the prices the station

charges are set exclusively by the company. This is what is commonly known as a dealer tank

wagon or DTW price. The price is usually tied back to a rack and includes delivery, since the major delivers the fuel itself.

The Lessee Dealer

Who Are They?

A lessee dealer does not actually own the real estate or the equipment. They lease or rent the space and absorb the costs of operating the station.

Usually – but not always – the lessee dealer gets into the brand relationship via a branded distributor, what is known in the business as a branded jobber. Essentially, the lessee dealer leases the real estate and, through the jobber, pays a fee back to use the brand name. They are usually locked into long-term contracts with the branded jobber and, by default, with the major oil company.

How Do They Buy Their Fuel?

The lessee dealer typically buys fuel directly from the major via the branded jobber. The price they pay is still the same basic formula: rack price + transportation to deliver into the station.

Here’s a big advantage for these guys – the lessee dealers often receive benefits from their major in the form of rebates and incentives – especially in markets that feature tight margins and stiff competition. These benefits often come in the form of “temporary voluntary allowances” or TVAs, which incentivize the dealer to push the fuel in times of oversupply.

The Jobber/Dealer

Who Are They?

“Jobbers” resell fuel – it’s a revenue center for their business. Their customer base is varied. It’s not just retailers. Jobbers also resell fuel to end users such as municipalities and government entities.

A jobber/dealer buys at the rack or on the spot market, if they have storage capacity to buy

bulk volumes. They then own a variety of stations, many of which may carry their own brand

(ex: “Sam the Jobber’s Gas”). This is considered an “unbranded” outlet.

They may also purchase station real estate and station assets outright from a major and sign an agreement to fly that major’s brand flag for a specific period.

Large resellers are among the most sophisticated of fuel buyers and are, in essence, oil companies without the “hardware,” (i.e., the refinery) with supply, trading and marketing arms. They are frequently called “superjobbers.”

How Do They Buy Their Fuel?

Jobber/dealers buy their fuel based on rack indices and buy fuel on the spot market level. That sets the basis for their retail price levels.

The Open Dealer

Who Are They?

This type of retailer, typically, is a private, independent station owner.

Sometimes, they become a jobber and redistribute fuel, but most of the time they are just retailers that own their own real estate. They own it all – the land, the pumps, everything.

Most times, they get supplied from local resellers and do not pull their own fuel at the rack. They usually have a contractual supply agreement with the local jobber, but unlike the jobber or the lessee dealer, their contract terms are usually shorter in length.

How Do They Buy Their Fuel?

The open dealer usually buys fuel from a jobber, who charges a “delivered” price to get it from the rack to the station. The open dealer will use that delivered cost as their basis and add in their own margin. A big challenge for these retailers is that they usually do not get help from their supplier in times of tight supply or when margins contract the way a retailer with a branded supply deal might. So, for them, competition is EVERYTHING!

Chain Retailers

Who Are They?

Chain retailers are companies such as Kroger, Walmart, Sam’s Club, Wawa, Costco and Safeway These are the big box stores.

These retailers have become among the newest and most influential players in the U.S. retail fuel landscape.

Chain retailers construct the stations on their own sites, so they own the entire station. Their stations also usually fly their own brand flag.

How Do They Buy Their Fuel?

Chain retailers buy an enormous amount of fuel, usually on a rack basis, but also on a spot basis. Remember – they are HUGE fuel buyers and most often are aggressive negotiators with their suppliers. Their fuel-buying operations are among the most sophisticated in the industry. They leave nothing on the table!

On the street, they often feature the most competitive prices in the market, using fuel as a loss leader to get the customer into the store.

Looking Ahead

The trends that shaped the current retail landscape are here to stay and OPIS market watchers fully anticipate:

- More refiners are going to divest themselves of retail sites and focus resources on other areas, such as exploration and refining.

- More hypermarketers are going to enter the market and further shake up competition.

- Jobbers are going to buy more stations and probably other jobberships, thus creating more superjobbers.

Conclusion

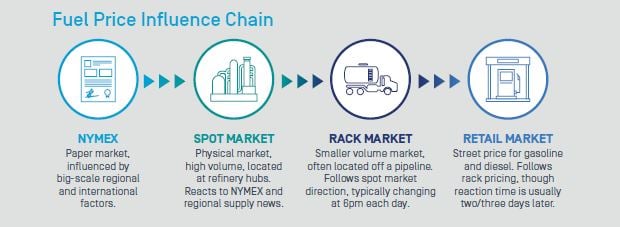

And – above all – the price influence chain will continue to ripple volatility down from the NYMEX, to the spot market, to racks and to the retail level.

Buying fuel is confusing – it’s not like stocking pencils or pens or paper cups. And with a market that moves in rapid-pace, it can be daunting to make the right decisions.

Understand the fuel chain from start to finish with this helpful e-Book from OPIS.